Git

What is Git

Git is a distributed version-control system for tracking changes in source code during software development. It is designed for coordinating work among programmers, but it can be used to track changes in any set of files.

Git lets us keep track of versions of our code, just like saving a Word document

Git lets us easily see differences between versions of code

Git does this in a distributed manner

Git is the defacto standard for VCS

It is a must for working with code in this day and age

Exercise

Create an empty directory we can work with

$ mkdir git_demo && cd git_demo

Check that it is empty

$ ls -a

. ..

Initialize a new repo

To have git track our code, we must tell git that it should create a new repository

Git Init

$ git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/anders/projects/git_demo/.git/

Now there should be something in your directory

$ ls -a

. .. .git

Open up the magic directory

Let’s have a quick peek under the covers

Look, don’t touch - You will (almost) never need to do anything in here

$ tree -a .git

.git

├── branches # Any branches are stored here

├── config # Any local configuration is here

├── description # used by gitweb

├── HEAD # points at the HEAD commit

├── hooks # Any scripts you want to run during the git lifecycle

├── info # Contains a local exclude

├── objects # The key-value database

└── refs # Stores the names of references

Let’s actually do some work and come back to this

Committing files

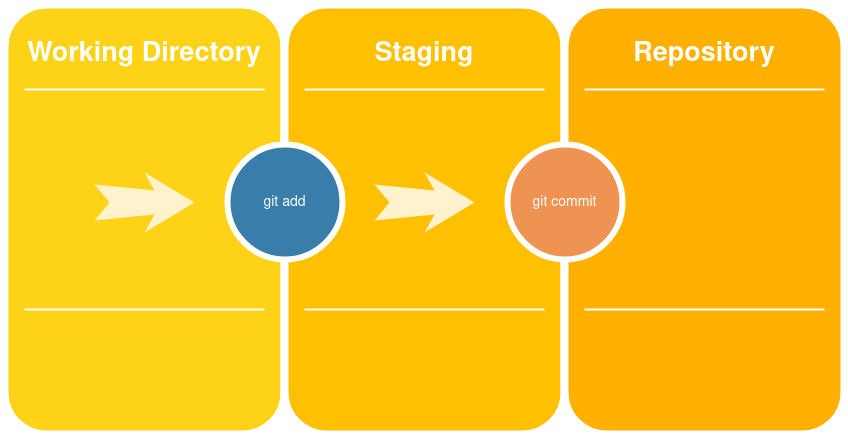

The git workflow

- git status

- git add

- git commit

Git status

git status gives us information about the current state of git

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

Notice it gives us an indication of what our next step might be

Exercise

Create a new file named example.txt and write some text

Git add

Now we have some text - run git status again

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

example.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

We have a new untracked file - untracked means git has not added it to it’s database yet

Let’s track the file

$ git add example.txt

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: example.txt

We are now ready to commit our file - aka “Press Save”.

We need to provide a commit message

A good commit message is a helper for yourself if you ever need to go back in time!

$ git commit

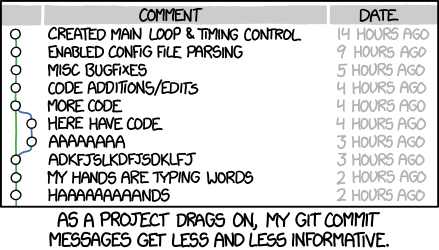

Aside - Commit messages

A good commit message should have a title - use verbs to describe what this commit will do!

Update/Add/Fix/Createetc

It should also have a descriptive body - a more detailed outline of what is happening

Don’t be this guy:

Where did our file go?

Update the file

Now that we have a file under version control, let’s change it

Exercise

- Update your example.txt with some additional text

- Add your new changes - don’t commit

- Run git status

- Add some more text to your file

- Run git status again

What do you think is happening?

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: example.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: example.txt

Since Git has the concept of the staging area, we can stage changes as many times as we want before committing.

- A change is not the same as a file

- Staging means selecting what changes we want to include in our next commit

Exercise

- Make commit

- Run

git status - Add the remaining changes

- Make another commit

Aside - .gitignore

Often we have files we don’t want git to keep track of such as editor configuration, large files or temporary files

These can be listed in a special .gitignore file in the same location as your .git directory and you should always have one!

A template for a python .gitignore file can be found here

Git branching

One of the reasons why Git has become popular is the cheap branching

It is very easy to make a branch to work in parallel

Create a new branch

$ git switch -c my_new_feature # -b means create the branch

Switched to a new branch 'my_new_branch'

$ git status

On branch my_new_branch

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git switch -c will create a new branch based on the branch where you are - e.g master in this instance

Exercise

- Add some more text to example.txt

- Add a new file example2.txt with some text

- git

addandcommitthe new changes

Switch between branches

$ ls

example2.txt example.txt

$ git switch master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ ls

example.txt

What happened to your files?

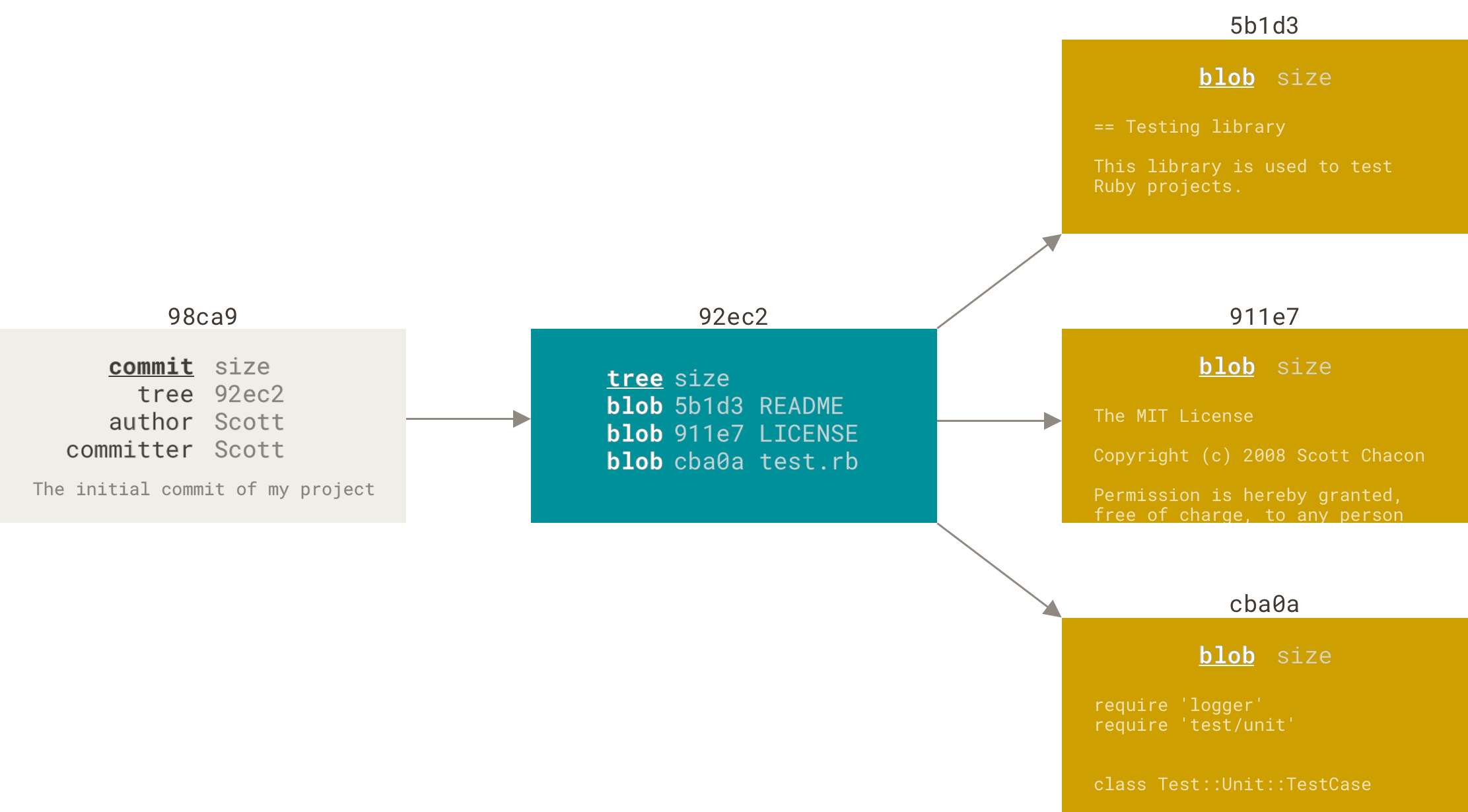

Interlude - the .git directory

Git is “just” a key-value store

When we commit - git saves our data and writes down an ID to where it is

When we change branches, git looks up what files it needs to get and simply replaces your working directory

We can see for ourselves

# Look up the ID of my_new_branch

$ cat .git/refs/heads/my_new_branch

1359962e527f4ab2c15c7703b233fb4e8a0afb83

$ cat .git/refs/heads/master

c26f7174f47f0781a8c4f83229d0c50b79a204c0

$ tree .git/objects # The actual files

.git/objects

├── 10

│ └── ba6b215ed96b95bef8d9e605b45fffe24efa95

├── 13

│ └── 59962e527f4ab2c15c7703b233fb4e8a0afb83 # Here's our branch ID

├── 43

│ └── e5d206cf6e3486c50e0c68329e2f4301cb8454

...

├── af

│ └── b164663e3655ebab9d07129cad85b046db6ae0

├── c2

│ └── 6f7174f47f0781a8c4f83229d0c50b79a204c0 # Here's our master branch

├── fb

│ └── a58de71fd101b35076d9eaa60ea954b139e03b

├── info

└── pack

/Aside

Combining branches

When we are happy with the extra code we wrote on my_new_branch we want to merge it into master

$ git switch master # Switch to master

$ git merge my_new_branch # Merge my_new_branch into master

Updating c26f717..1359962

Fast-forward

example.txt | 2 ++

example2.txt | 1 +

2 files changed, 3 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 example2.txt

$ ls

example2.txt example.txt

Note that my_new_branch is untouched by the merge

Delete the branch

Now that we are done with the branch, we can delete it

$ git branch -d my_new_branch

Deleted branch my_new_branch (was 1359962)

This only deletes the reference - the file found in .git

$ ls .git/refs/heads

master

The database of files is still intact (our .git/objects directory)

Version Controlling

The whole point of a VCS is to be able to navigate between versions and we have a few ways to do that in git

Examine the history

$ git log

commit 1359962e527f4ab2c15c7703b233fb4e8a0afb83 (HEAD -> master)

Author: Anders Bogsnes <andersbogsnes@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Aug 10 15:03:13 2020 +0200

Committing to my branch

commit c26f7174f47f0781a8c4f83229d0c50b79a204c0

Author: Anders Bogsnes <andersbogsnes@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Aug 10 14:46:27 2020 +0200

My third commit

commit 90b8e5126da798b6e217f8dbdb3ec4354f534955

Author: Anders Bogsnes <andersbogsnes@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Aug 10 14:32:05 2020 +0200

Second commit

commit 722b3172cabe09b98d54ad91d9ceddd4c31e86aa

Author: Anders Bogsnes <andersbogsnes@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Aug 10 14:19:00 2020 +0200

Initial commit

A shorter version

$ git log --oneline

1359962 (HEAD -> master) Committing to my branch

c26f717 My third commit

90b8e51 Second commit

722b317 Initial commit

The number on the side is called the

SHA- it’s theIDgit uses, that we saw beforeWe can refer to a commit by it’s

SHAand we only need a few digits, enough to be unique

Timetravel with git

$ cat example.txt # Look at my file

My test file

Now has a more descriptive body

And some more texto

Fourth line of text

$ git switch -d 722 # Go back in time to SHA 722

$ ls

example.txt # No example2.txt!

$ cat example.txt # Look at the file again

My new text file # What I wrote in my file when I created it

$ git switch - # Go back to newest version of master

Restore a file

We can change a file to the way it looked before

$ git restore example.txt -s 722 # Restore the file from revision with SHA 722

$ ls

example2.txt example.txt

$ cat example.txt

My new text file

$ git status

On branch master

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: example.txt

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

>>> git restore example.txt # Return the file to newest version of master

Undoing a commit

We often want to undo everything from one commit at a time

For example, we want to rollback a new feature which is bugged

We can do that in two ways:

- git reset

- git revert

Git revert

Create a new commit that does the opposite of the specified commit

$ git log --oneline

* 1359962 (HEAD -> master) Committing to my branch

* c26f717 My third commit

* 90b8e51 Second commit

* 722b317 Initial commit

$ git revert 135

Removing example2.txt

[master 0f7f27d] Revert "Committing to my branch"

2 files changed, 3 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 example2.txt

$ ls

example.txt

Revert is most often used when we have published our changes and don’t want to change the history

We will talk more about publishing later

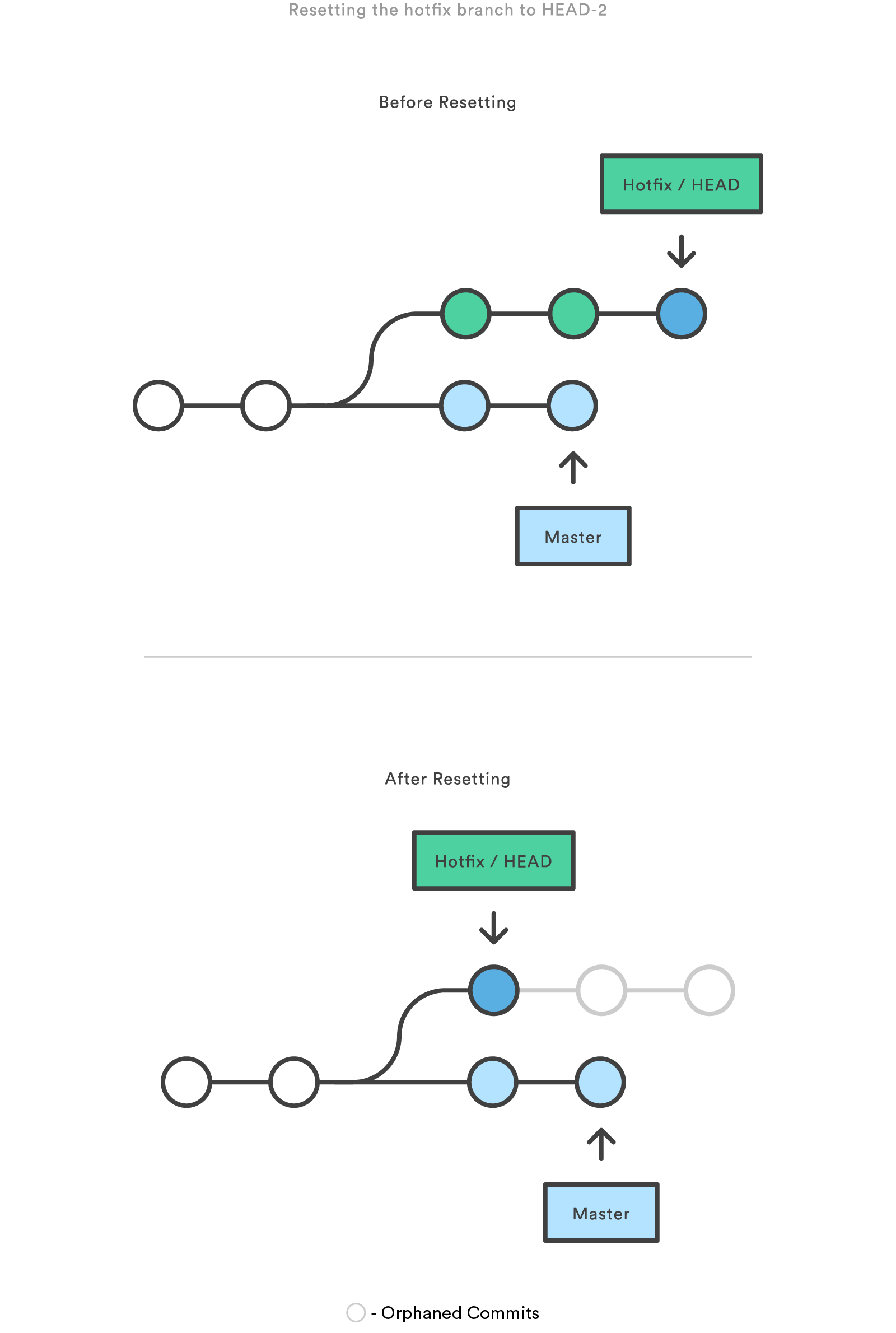

Git reset

Chop out all commits after the specified one. Resets the history as if that revision is the newest

$ git log

0f7f27d (HEAD -> master) Revert "Committing to my branch"

1359962 Committing to my branch

c26f717 My third commit

90b8e51 Second commit

722b317 Initial commit

$ git reset 1359

Unstaged changes after reset:

M example.txt

D example2.txt

$ git log

1359962 (HEAD -> master) Committing to my branch

c26f717 My third commit

90b8e51 Second commit

722b317 Initial commit

This is a bit harder to undo as our label is now pointing to a different commit - the other commits are orphaned

If you are unsure you’re doing it right - write down the SHA of the commit you’re currently on - that way you can always get back

Reflog

We can also see a history of when we changed HEAD (our current location) by using git reflog

$ git reflog

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{0}: checkout: moving from 1359962e527f4ab2c15c7703b233fb4e8a0afb83 to master

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{1}: checkout: moving from master to 1359962

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{2}: reset: moving to 1359962

0f7f27d HEAD@{3}: revert: Revert "Committing to my branch"

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{4}: reset: moving to HEAD@{3}

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{5}: reset: moving to HEAD@{2}

90b8e51 HEAD@{6}: checkout: moving from master to master

90b8e51 HEAD@{7}: reset: moving to 90b8e51

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{8}: checkout: moving from 722b3172cabe09b98d54ad91d9ceddd4c31e86aa to master

722b317 HEAD@{9}: checkout: moving from master to 722b317

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{10}: checkout: moving from 722b3172cabe09b98d54ad91d9ceddd4c31e86aa to master

722b317 HEAD@{11}: checkout: moving from master to 722b317

1359962 (HEAD -> master) HEAD@{12}: checkout: moving from 722b3172cabe09b98d54ad91d9ceddd4c31e86aa to master

Then we can do git switch as normal

Fixing detached state

When we switch to a given commit, git warns us

You are in 'detached HEAD' state. You can look around, make experimental

changes and commit them, and you can discard any commits you make in this

state without impacting any branches by switching back to a branch.

If you want to create a new branch to retain commits you create, you may

do so (now or later) by using -c with the switch command. Example:

git switch -c <new-branch-name>

Or undo this operation with:

git switch -

Git is lettting us know that we are no longer on a branch, so any changes we make won’t have a label (unless you write down the SHA)

If we want to put a label on the commit, we can use switch -c to create a new branch or we can get back to labelled territory with

git switch - to take you back to the last branch you were on

Exercise

- Switch to an earlier commit

- Create a new branch from that commit

- Make a change to a file

- Add and commit that change

- Go back to master

- Run

git log --graph --all --oneline

Where is your new branch coming from?

Git Flow

Git is a flexible tool, and many different workflows have built up around how to use git when working in teams

Git flow is one such workflow which has become very popular.

The branches

Git flow has five main types of branches

- master

- develop

- feature

- release

- hotfix

Master

- Always contains the code that is in production

- This is the branch we deploy to production

Develop

- Where the newest features are included, but is not yet released

- Should generally be ready to release

- The branch we merge into when our features are done

- Where features branch from

Feature

- Represents a new unit of work we want to do

- Should be short-lived and contain only the code necessary to implement the new feature

- One issue/feature per feature branch

- Merged into develop

Release

- Created to release a new version

- Represents a release

- Generally only bump version number

- Merge into master and develop

Hotfix

- Only for critical bugs that can’t wait for a new release

- Based off of

masterand notdevelop - Is merged into

masteranddevelop

Vincent Driessen@nvie.com

Benefits

- Feature workflow makes it easy to do code reviews

- Having a dedicated production branch makes it easy to see what was in production when

- Easy to collaborate on new features

Negatives

- Lots of branching

- Only enforced by convention

Additional resources

The Central repository

When working with others, we want a central repository that we synchronize our local repository with

That way, we can share our changes easily!

The main players

The main companies offering these services are

- Github (bought by Microsoft)

- Gitlab (independent)

- Bitbucket (Atlassian)

- Azure Devops? (old Team Foundation Server)

For this workshop, we will use Gitlab

Setup gitlab.com

Everyone will need a gitlab.com account

- Setup an account at gitlab.com

- Setup ssh keys (under Settings/SSH Keys - follow the instructions to generate new ones)

Pair up two and two (or three). Do the rest of the exercise on one machine

Exercise

- Create a new directory on your machine called

calculator - In that directory, create a new file called

calculator.py - Define a function

add(a, b)that returns the sum of a + b - Run git init, add and commit

- Create a new project in Gitlab called calculator - set it to public and don’t click “Initialize repository with a README”

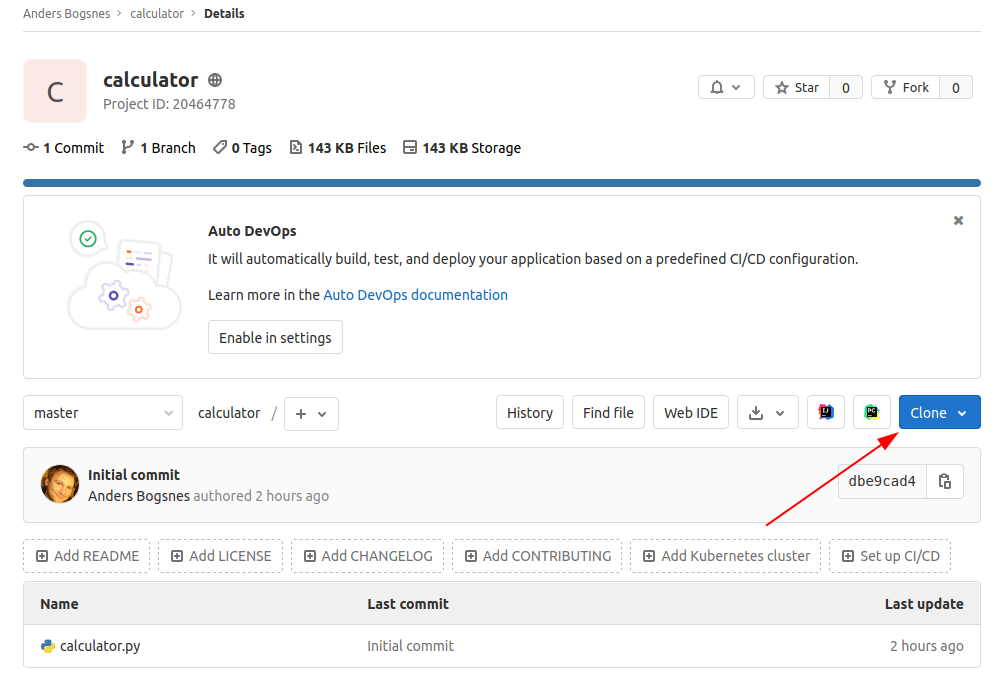

Linking local repo to Gitlab

We need to tell git about our remote repository

$ git remote add origin git@gitlab.com:andersbogsnes/calculator.git

Creates a label origin 👉 my_long_url_i_cant_remember

Push - Update remote from local

$ git push -u origin master

I want to push my changes from my local branch to the branch named master at the url specified in origin and I want to link these two branches (-u)

Set up a develop branch

- We want to practice git flow, so we need a develop branch

# Create a new branch called develop and switch to it

$ git switch -c develop

# Push local branch develop to origin's develop branch

$ git push -u origin develop

- Go to gitlab and set development as your default branch (Settings/Repository)

Exercise

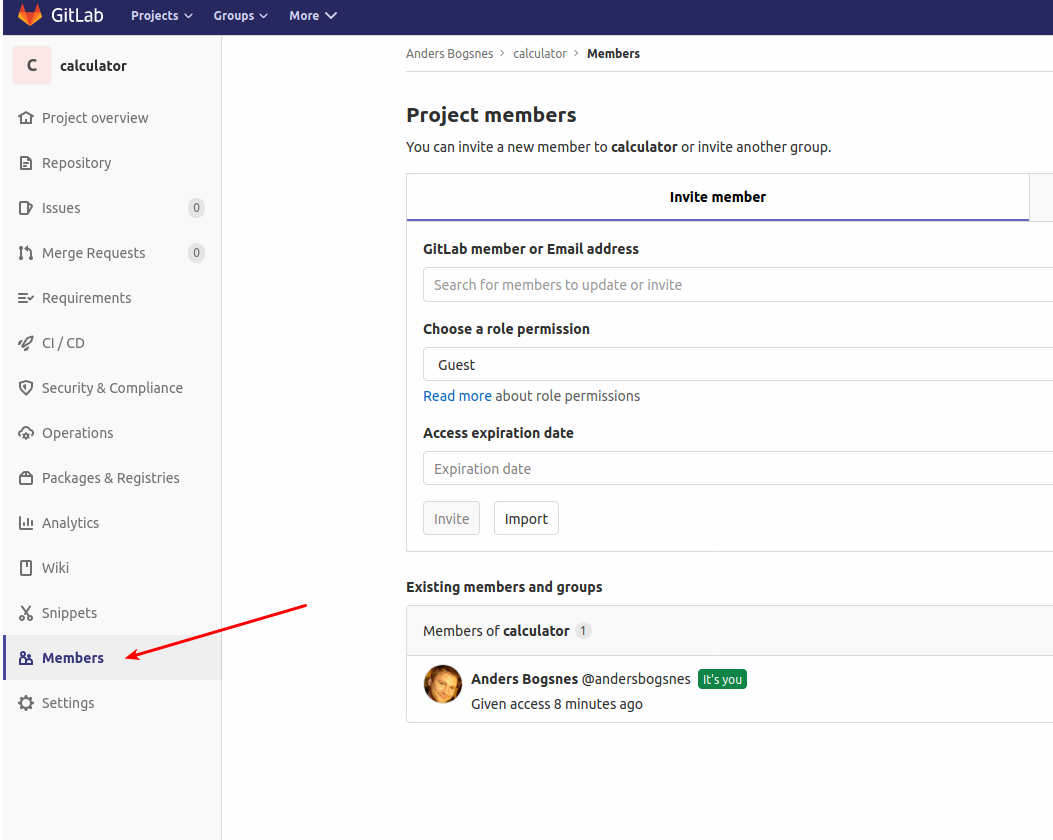

Add your partner to your repo

Clone the repo

Your partner should now clone the repo

$ git clone git@gitlab.com:andersbogsnes/calculator.git

clonecreates a full copy of a repository to have locally- We are only copying files back and forth - there is no other link!

Exercise

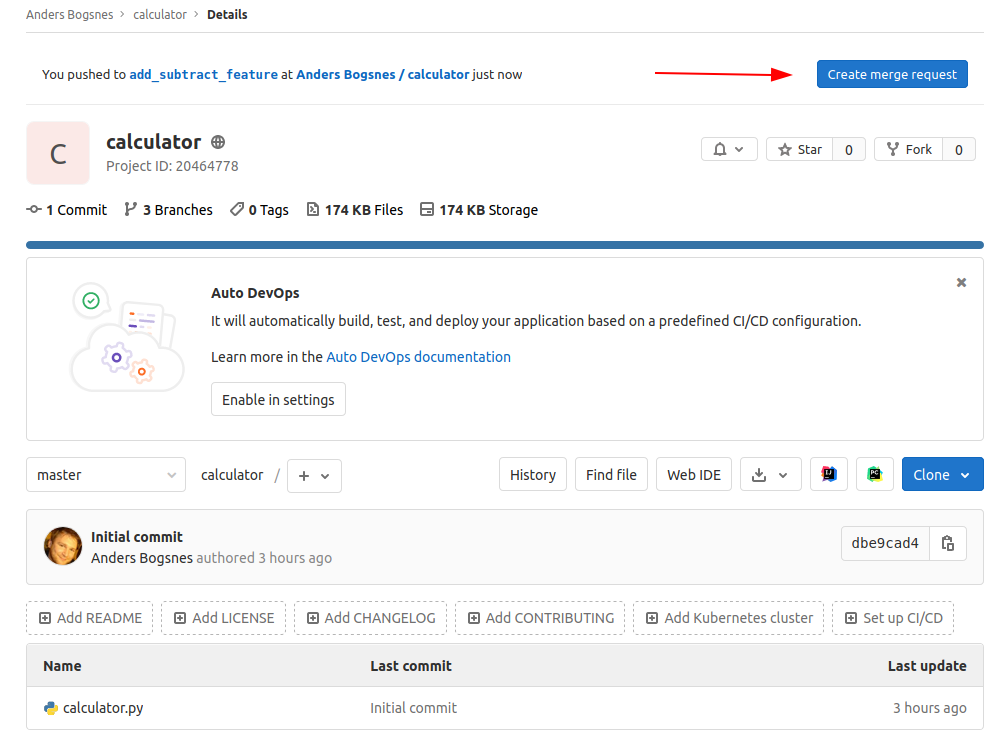

One person

- Create a new feature branch

- add a new function

subtract(a, b)which subtracts two numbers - push the new branch to gitlab

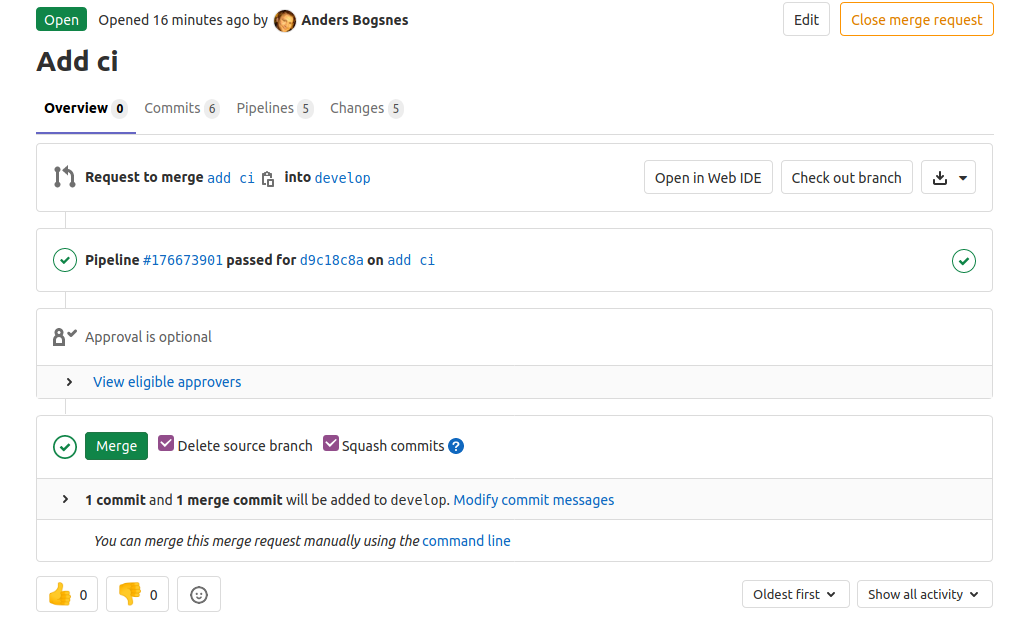

- create a merge request

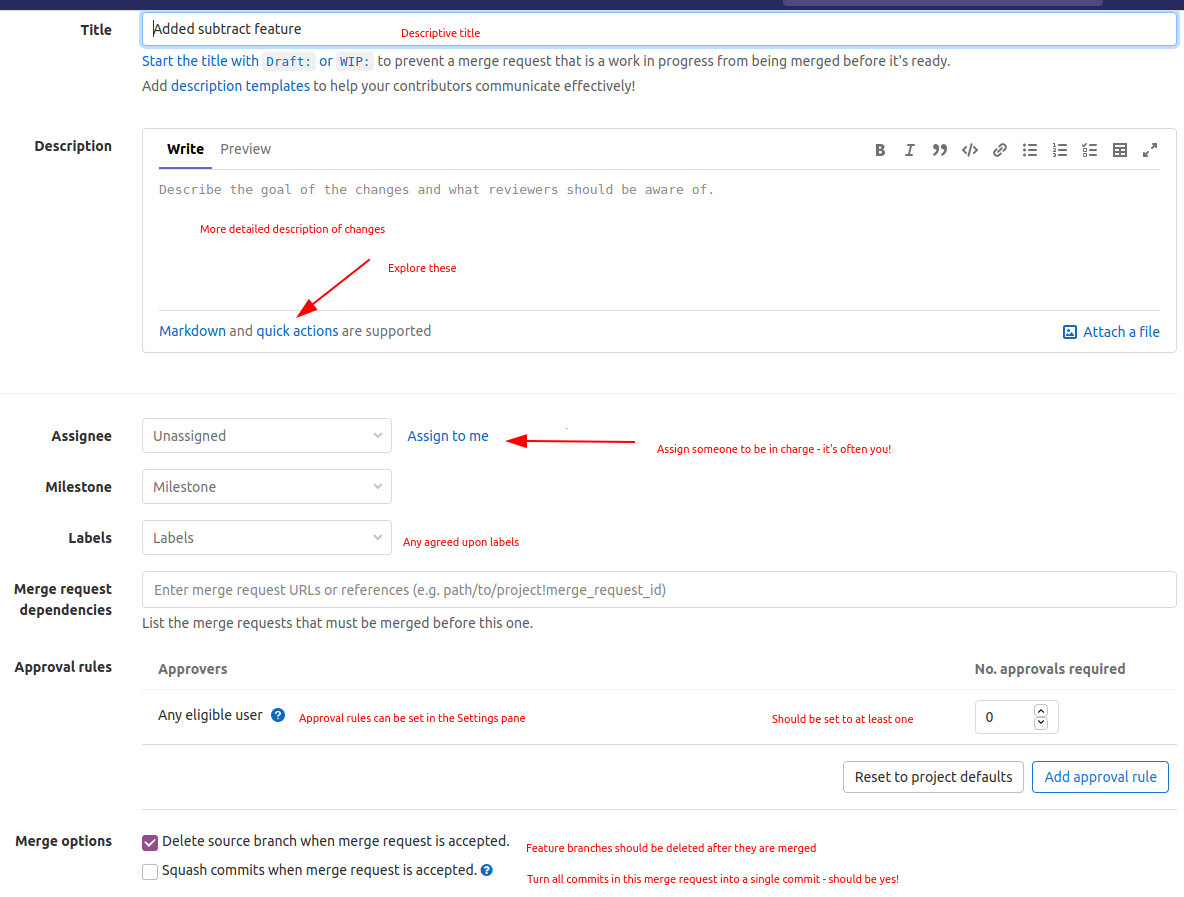

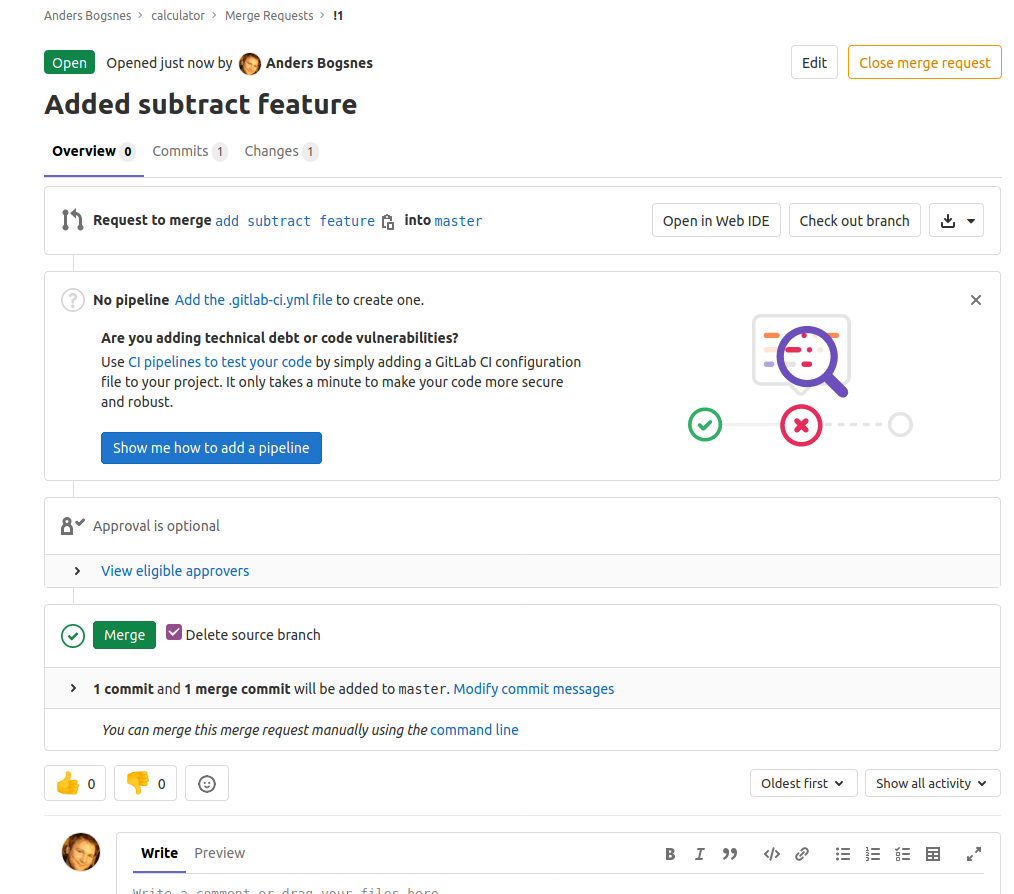

Merge requests

Github calls it a merge request, everyone else calls it a pull request

Creating a merge request

Ready for review

Exercise - 1 min

One person

- Click on changes

- Make a comment on the code

- Resolve the conversation

- Make another comment on the code

- Resolve the comment in a new issue

- Merge the request

Git pull

There are new changes in the central repository so we need to update our local repository to get the changes

Central vs local repository

- You have two separate copies of the repository, one local and one in the central repository

git pullwill asks the central repo if it has any commits that are not present locally- If it does, git will do a

merge, merging the new commits into your local commits

CI/CD

Integration and Deployment

- Integration means adding new code to our codebase

- Deployment means deploying new code to production

CI/CD providers

Many providers in the market

- Travis

- CircleCI

- Jenkins

- Github Actions

- Azure Pipelines

- Gitlab CI/CD

- Argos

Integration

Gitlab has CI/CD built-in and we are going to add some integration steps

When new code is pushed to gitlab, we want to

- Lint the code

- Run unit tests

The config file

Gitlab looks for a file named .gitlab-ci.yml which describes what jobs to run

image: python:3.8.5-slim # What docker image to use

lint: # a job name - can be anything

script: # A list of commands to run

- pip install flake8

- flake8

test:

script:

- pip install pytest

- pytest

Exercise

- Add the .gitlab-ci.yml to a new branch

- Push the new branch

- What happens?

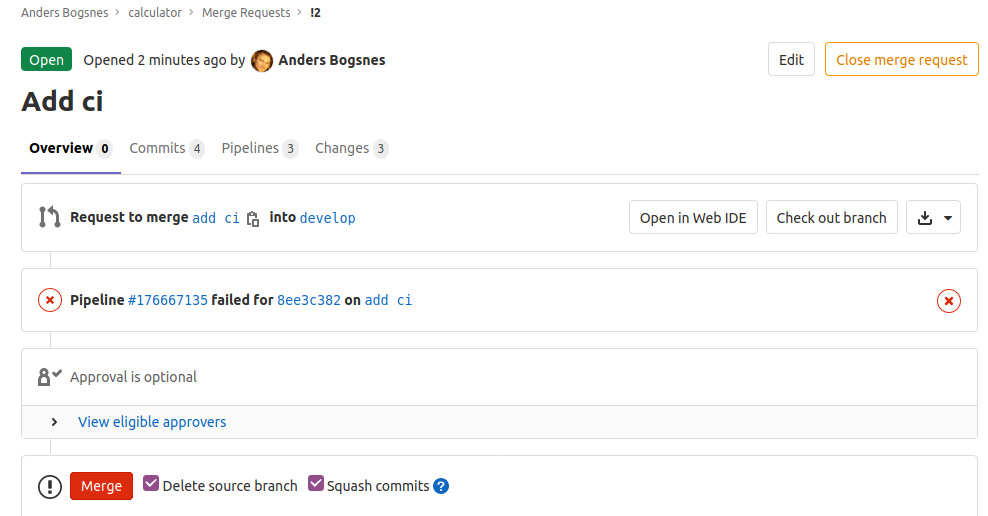

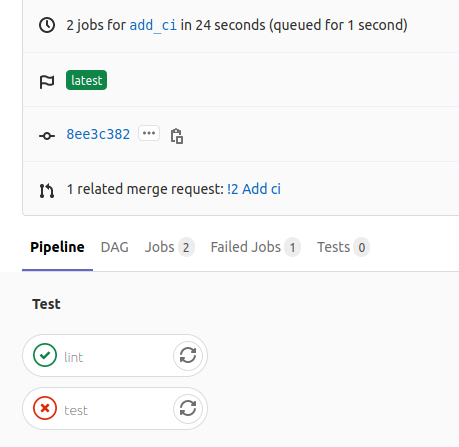

A failing pipeline

Pipeline overview

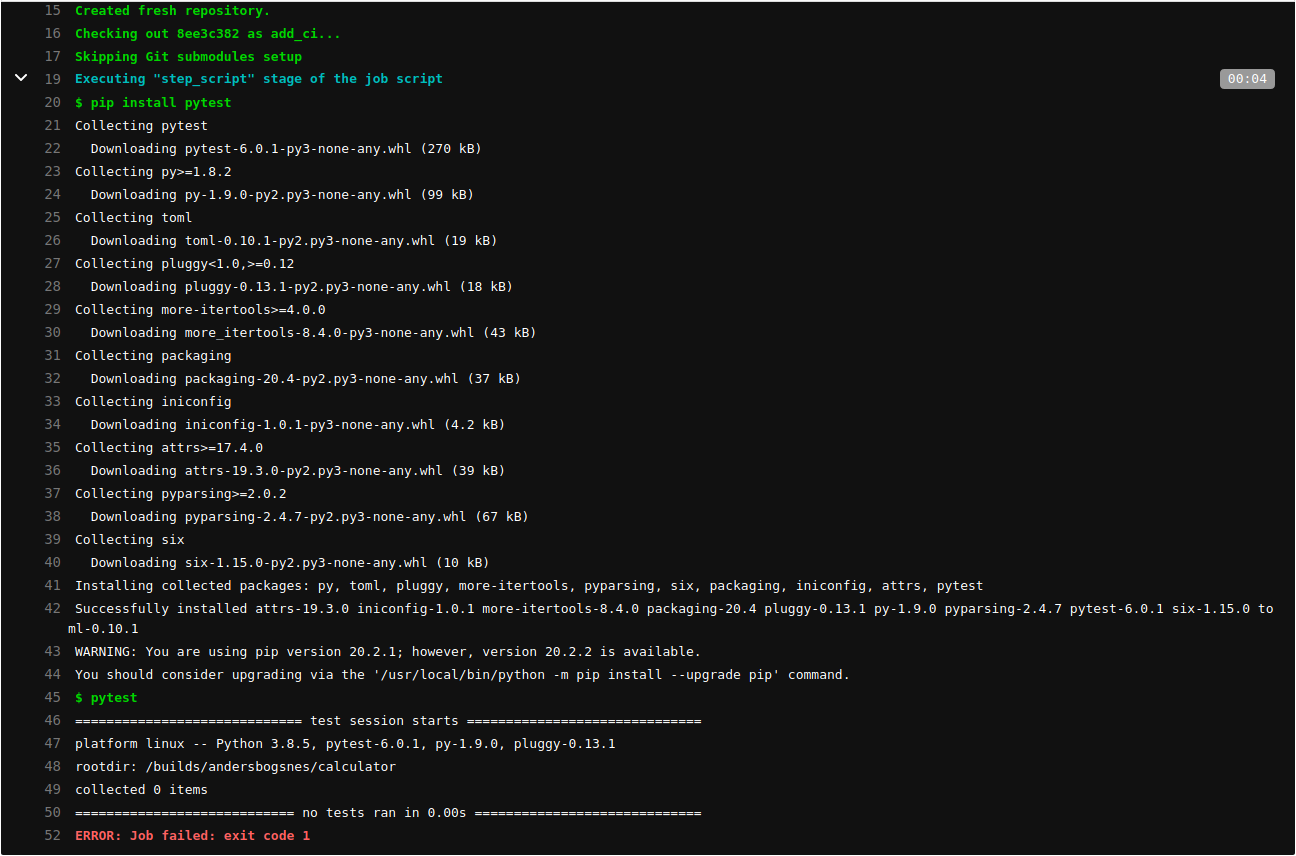

Pipeline logs

Aside - exit codes

Exit codes is a number returned by a command-line program

- 0 is good

- Not 0 is bad

Fix failing CI

We need to write some tests!

Exercise

- Create a

test_calculator.py - Write some tests for the add function

- Write some tests for the subtract function

- Git add, commit, push

- Get to a passing pipeline!

Happy pipeline

Happy team

With CI turned on, your teammates can be confident that the code in develop and master is tested and linted

- Reduces errors

- Reduces codereview (we don’t codereview failing code!)

- We know that when we deploy, our code is passing all tests

Exercise

- Add pytest-cov coverage to CI

- Add black formatting

- Add mypy (and type hints)